This document has been prepared by the ACCC, ACMA, eSafety Commissioner and OAIC (member regulators) in their capacity as members of the Digital Platform Regulators Forum (DP-REG). The information in this publication is for general guidance only. It does not constitute legal or other professional advice, and should not be relied on as a statement of the law in any jurisdiction. Because it is intended only as a general guide, it may contain generalisations. You should obtain professional advice if you have any specific concern.

The member regulators have made every reasonable effort to provide current and accurate information, but do not make any guarantees regarding the accuracy, currency or completeness of that information.

Parties who wish to re-publish or otherwise use the information in this publication must check this information for currency and accuracy prior to publication. This should be done prior to each publication edition, as member regulator guidance and relevant transitional legislation frequently change. Any queries parties have should be addressed to the DP-Reg@oaic.gov.au

1. Background

This paper examines Large Language Models (LLMs). It is the second public paper prepared as part of the Digital Platform Regulator Forum (DP-REG)’s joint work to understand digital platform technologies and their impact on the regulatory roles of each DP-REG member agency.

The first part of DP-REG’s work examined the harms and risks of algorithms. This paper supports DP-REG’s 2023/24 strategic priorities, which involve evaluating the benefits, risks and harms of generative AI, along with its relevance to the regulatory responsibilities of each DP-REG member. It also aims to increase collaboration and capacity building among the four members to deepen our knowledge of technology, which can support the future work of individual regulators and DP-REG.

New services powered by LLMs have significant potential to benefit consumers and boost productivity. This technology can be applied in various ways to enhance the quality of goods and services for consumers and improve efficiency and productivity in sectors such as programming, legal and support services, education, academia, media and public relations. It also has the potential to enhance digital literacy and create positive online experiences for all Australians.

However, the use of these models carries risks, including increased exposure to harmful content such as misinformation, abusive or exploitative content, manipulation, coercion, scams and fake reviews. There are also concerns related to anti-competitive behaviour and threats to privacy and safety due to the collection and use of personal data.

While LLMs will likely intersect with a wide range of legal and regulatory issues, such as copyright and anti-discrimination laws, this paper specifically addresses how LLMs intersect with the regulatory responsibilities of DP-REG members, which include consumer protection, competition, the media and information environment, privacy and online safety.

The paper outlines the challenges presented by LLMs in each of these areas but does not consider the specific application of Australian laws to the issues raised by LLMs or propose reforms. DP-REG member regulators are monitoring and considering developments related to LLMs in line with their individual regulatory responsibilities (outlined further at 4.1 below).

Other government activities on generative artificial intelligence (AI) in Australia include the Department of Industry, Science and Resources’ (DISR) ‘Safe and Responsible AI in Australia’ consultation, and the House Standing Committee on Employment, Education and Training’s inquiry into the use of generative AI in the Australian education system. DP-REG’s joint submission to DISR’s ‘Safe and Responsible AI in Australia’ consultation, provided in attachment A, offers a closer look at how the regulatory frameworks of DP-REG members apply to LLMs and generative AI more broadly.

2. Description

LLM technology has advanced rapidly due to the availability of more training data, enhanced artificial neural networks with larger datasets and parameters, and greater computing power. This could impact almost every aspect of our lives, in both positive and negative ways.

The public release of LLM chatbots such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT in late 2022 or Microsoft’s new Bing in 2023 has generated huge interest in the potential benefits and risks of LLMs. The significant industry and public interest in this technology is reflected both in the volume of media coverage on these emerging services, and in the fact that many major digital platform firms have launched or are testing their own LLM products. This includes Amazon, Apple, Baidu, Google, Meta, Microsoft, Open AI, Snap and X (Formally Twiter).[1]

This development has the potential to influence the availability of digital platform services, bringing benefits but also introducing and exacerbating online risks. This paper explores the possible implications of this technology for consumer protection, competition, the media and information environment, privacy, and online safety.

3. Key insight questions

3.1 What are Large Language Models?

LLMs are a type of language model[2] that form the basis of certain generative AI systems,[3] a subset of ‘artificial intelligence’ or AI.[4] These terms can be contested and difficult to define.[5]

LLMs, like other generative AI models, produce outputs based on inputs or ‘prompts’. They use algorithms trained on vast amounts of data, primarily text in the case of LLMs. This training helps them predict and approximate relationships between data. In simpler terms, if you give an LLM some words to start with, it can predict what characters or words might come next, much like the ‘auto complete’ functionality in many smartphone messaging apps.

The results generally appear original, even though they are essentially a synthesis of the existing data used to train the LLM, including direct excerpts from that data.

This ability allows LLMs to power ‘chatbots’ that can mimic conversations with users in natural language and generate text that appears ‘human-like’. Examples of LLM chatbots include AliBaba’s Tongyi Qianwen, Baidu’s Ernie 3.0, Google’s Bard (which incorporates its PaLM 2 LLM), Meta’s LLaMA and LLaMA 2, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, and Microsoft’s new Bing search engine (which incorporates OpenAI’s GPT-4 model)[6]. Platforms such as Amazon (through Amazon Bedrock)[7] and Microsoft (through Azure AI)[8] have also started to leverage their cloud operations to sell various LLM technology services.

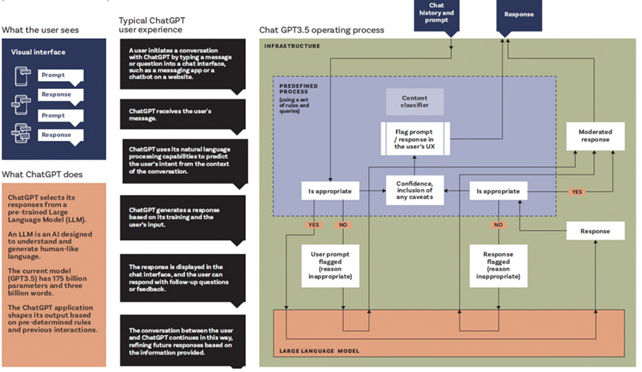

Example LLM user experience (based on ChatGPT-3)

3.2 How does the technology work?

To be effective, sophisticated LLMs need vast amount of training data. For example, GPT-4 uses about 1 trillion parameters according to some sources)[9]. The training process also demands a significant amount of computing power.

Most LLM chatbots can only provide answers based on the information they have been trained with, usually large amounts of data collected from the web. However, others, such as GPT-4, can connect to the internet via plugins to search for new information.

This is what happens when a user enters a prompt into an LLM chatbot:

- The model turns the prompt into a series of numbers that capture the relevant information about the query (encoding). These numbers are structured so related or similar queries have similar values. In some models, this string of numbers captures both the user’s query and the conversation history for context.

- These numbers are processed through the LLM’s mathematical equation, which is encoded as a ‘neural network’ made up of layers of ’nodes’. Each ‘node’ takes in numbers, applies weights (the model’s parameters) and returns a result.

- As the numbers pass through the layers of the network, they transform from the input numbers to the output numbers.

- At the end of the network, a final set of numbers comes out from a final layer of nodes, known as the output layer.

- The numbers from the output layer are converted back into text (decoding).

- In some chatbot systems, there is then a validation step to ensure the text does not contain offensive or prohibited content.

- Finally, the chatbot sends the text back as a response to the user.

Some LLM developers may publish ‘model cards’ or ‘system cards’ about their products. These cards explain how the LLMs work and outline potential use cases and risks associated with misuse.

For example, in March 2023, OpenAI published a system card for GPT-4 outlining some of the safety challenges and what steps OpenAI had taken to address them.[10] However, LLM developers, including OpenAI, have faced criticism for a lack of transparency in how their LLMs operate, such as not disclosing the datasets used to train them. One critic described the GPT-4 system card as ‘lacking in technical detail’ and ‘disclos[ing] none of the research.’[11]

3.3 What are the applications of the technology?

LLMs can do many things and offer benefits to a wide range of industries. For example, LLMs can:

- create content, such as emails, essays, news stories, speeches, creative works, language translation, press releases, and customer service chatbots

- find information, such as articles and books

- summarise information quickly, or turn bullet points into full text

- write and debug programming code

- analyse data by identifying data sources, formatting and cleaning data, and creating charts.

These capabilities are expanding and can be used in digital platforms such as gaming platforms, search engines, social media, websites, as well as in programming, education and academia, legal and support services, health, customer service, journalism, creative sectors, and the public sector.

3.4 What are the limitations of the technology?

LLMs don’t really understand the information or language in their inputs and outputs. For example, the 2022 paper ‘On the Danger of Stochastic Parrots’ notes that text generated by an LLM lacks a true understanding of communication, the world, or the reader’s state of mind. As the paper says, the generated text ‘is not grounded in communicative intent, any model of the world, or any model of the reader’s state of mind’. However, users tend to think LLMs understand like humans do, due to ‘our predisposition to interpret communicative acts as conveying coherent meaning and intent, whether or not they do.’[12] This can lead to LLM chatbots producing information that might be inaccurate or harmful while also appearing authoritative.

The effectiveness of generative AI models depends on the availability of human-created training data. This data may be limited and could cause privacy concerns, leading to the use of synthetic data (AI-generated data) for model training. Still, there are concerns that AI models trained on synthetic data, including LLMs, may be vulnerable to ‘Model Autophagy Disorder’, causing precision and recall to progressively decrease in a ‘self-consuming loop’.[13]

3.5 What are the projected trends in usage, adoption and development of the technology?

There are strong indications and forecasts of rapid and widespread adoption of generative LLM-powered services. For example:

- ChatGPT, released in November 2022, gained rapid popularity, reportedly reaching 1 million users in 5 days,[14] 100 million active users by January 2023[15] and 1.6 billion site visits in March 2023, surpassing Bing.[16]

- Microsoft’s Bing experienced a 15.8% increase in traffic between 7 February 2023 (when it unveiled the LLM-powered ‘new Bing’) and 20 March 2023.[17]

- The global generative AI industry is expected to exceed US$100 billion per year by 2030,[18] with a more recent projection (April 2023) suggesting US$51.8 billion as early as 2027.[19]

- Microsoft and the Tech Council of Australia have estimated that rapid adoption of generative AI could add up to A$115 billion annually to the Australian economy by 2030.[20]

Specialised skills will be needed to harness the opportunities offered by this technology. A report commissioned by Australia’s National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) says that over the next 2 to 5 years, domestic and international competition for workers with digital technology capabilities is expected to be ‘a key risk for Australia’.[21]

3.6 Debate about risks associated with the technology

There is ongoing debate about the risks of LLM technology. Right now, LLMs and other forms of generative AI are attracting significant attention from media and the public. Headlines range from ‘Advanced AI could kill everyone’[22] to ‘5 Unexpected Ways AI Can Save the World’.[23] Industry leaders, such as Google DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, signed an open letter in May 2023 that describes ‘the risk of extinction from AI’ as a ‘global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war’.[24]

However, this focus on the theoretical ‘existential risk’ of AI systems may make people think the current technology is more useful and powerful than it really is. It could also distract attention from the more immediate and tangible risks posed by this technology.[25] You can find more about broader AI risks in the DISR Responsible AI discussion paper (see Section 5.1).

4. Potential impacts in regulated areas

4.1 Overview

LLMs have a broad range of applications and potential impacts within each DP-REG member’s regulatory remit. This includes:

- The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s responsibilities for regulating consumer protection (see section 4.2) and competition (section 4.3)

- The Australian Communications and Media Authority’s responsibilities for regulating communications and media services and some online content (section 4.4)

- The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner’s responsibilities for regulating privacy law (section 4.5), and

- The eSafety Commissioner’s responsibilities for regulating online safety (section 4.6).

DP-REG acknowledges that there is a broad range of cross-cutting issues, such as bias and discrimination, that are not covered within this paper.

4.2 Consumer protection

4.2.1 Scams, fake reviews and harmful applications

Public commentary and research point to multiple ways LLMs may be used for scams.

- ‘Phishing’ scams trick victims into giving away personal information such as bank account numbers, passwords or credit card numbers. They often pretend to be from trusted organisations such as banks and use generative AI to increase the volume and sophistication of campaigns (while reducing the effort and cost required to run these campaigns). This includes:

- feeding genuine messages from trusted organisations into models to create text that impersonates organisations with greater accuracy[26]

- improving the quality of grammar and spelling in phishing/scam messages[27]

- altering the tone of messages to better emulate the style and sophistication of real communications, making action from consumers more likely[28]

- generating seemingly authentic ‘spear-phishing’ emails, which may be targeted at specific groups or communities using relevant keywords, or at individual users based on their social media posts.[29] LLMs could also be used to extend spear-phishing attacks beyond single emails, continuing an entire conversation with a user to elicit information or trick the user into falling for the attack.

- These tools may also be used to increase the volume and sophistication of romance scams.[30]

- There is an emerging market of potentially questionable AI products claiming to be useful implementations of LLMs being advertised and sold on social media[31] which may mislead consumers.

- Scam chatbots could become more effective by using LLMs. Currently, many scams start with a human-bot interaction, before the bot sends a refined pool of potential victims to human scam operators. More realistic and human-like bots are likely to trick more people.[32]

- Since LLMs can also generate code, they could enable malicious users without sophisticated programming skills to write code creating malware.[33] Usage policies typically do not allow such malicious uses.[34] However, researchers have found loopholes which could be used to exploit LLMs for these nefarious purposes[35] as well as ways users can defeat ‘guardrails’ meant to prevent the harmful use of LLMs.[36]

- AI is being used to improve phone-based scams by making digital voices sound more realistic,[37] and text-to-audio generative AI could further facilitate audio-based scams.

- AI, including LLMs, might be used to create higher-quality fake websites, more easily replacing ‘lorem ipsum’ placeholder text with seemingly genuine content,[38] or more easily plagiarising content from legitimate websites. LLMs are already in widespread use to create low-quality ‘content farm’ websites that can earn advertising revenue for their creators by paraphrasing content from other sites, inserting many advertisements, and optimising the website keywords to get on the first page(s) of a search engine.[39] This trend is already making it more difficult for users to find good quality and authoritative content on the internet.

- LLMs might be used to generate higher-quality fake documents for scams. Many social engineering scams which result in large consumer losses involve fake official documents implying the scammer has existing funds or that the victim is legally protected. The quality of these documents vary, but LLMs are likely to increase how convincing they appear.[40]

LLMs may also be used to increase the volume and sophistication of fake reviews online. Previous ACCC Digital Platforms Services Inquiry reports say such bogus reviews can frustrate consumer choice, distort competition and erode consumer trust in the digital economy.[41]

4.2.2 Misleading and deceptive conduct

LLMs and other generative AI applications have been described as ‘extremely useful yet fundamentally fallible’. They are ‘particularly prone’ to risks stemming from system failures, malicious or misleading deployment, and overuse or reckless use.[42] For example, LLMs can provide false yet authoritative-sounding statements that could mislead users. There has been widespread media reporting about examples of mistakes made by ChatGPT and Bard;[43] this could extend to misleading information when consumers are making purchasing decisions.

Also, because LLMs are becoming more popular, they are generating a lot of hype. This might encourage false and misleading claims about a wide range of products that use AI. In February 2023, the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) published a blog post warning marketers against:[44]

- exaggerating the capabilities of AI products

- promising AI products do things better than non-AI products without adequate proof

- labelling products as ‘AI-enabled’ when they do not use AI technology.[45]

Compared to traditional search engines, LLM chatbots or LLM-based search engines may pose a greater risk of misleading consumers or facilitating scams. They might provide a single authoritative-sounding but potentially incorrect response to a query, as opposed to producing a more varied list of websites to investigate.[46]Removing the usual indicators of information quality, such as sources, exacerbates this risk. This highlights the need for users of these tools to consider their outputs critically. It also suggests consumers who lack understanding of the limitations of this technology may be disproportionately affected by its risks.

4.3 Competition

Developing and operating LLMs requires large sums of money upfront, access to vast datasets, long development lead times, sophisticated AI systems and talent, and substantial ongoing computing costs. These models are likely to have features common to digital platform services that make them tend towards concentration. These include a positive feedback loop involving collection and use of user data, economies of scale, and access to large volumes of high-quality user data. Because of these characteristics, new entrants could find it difficult to compete with digital platform services that use LLMs as part of new and existing services.

People have noted in public discussions and research that certain characteristics might give existing ‘big tech’ firms a competitive advantage in creating and releasing LLMs. These include:

- Data advantage: The output of LLMs becomes more accurate as the size and quality of training data increases.[47] However, beyond a certain point, the cost of building such large models and datasets leads to diminishing returns.[48] While open-source training data for general LLMs is available through digital libraries, firms with pre-existing access to the best and largest data-sets may benefit from first-mover advantage when creating LLMs. Many technology companies have focused on expanding their data advantage through strategic acquisitions. This has allowed them to establish strong positions in a range of industries.[49] LLMs developed by smaller start-ups or other firms may have less access to training data. This makes them more prone to mistakes and ‘hallucinations’,[50] making it more difficult for these firms to compete with the large digital platforms. Proprietary data is increasingly seen as a valuable (and monetisable) asset for existing and emerging niche LLM datasets. Companies such as Bloomberg, Reddit and X (formerly Twitter) are closing off open access to data that can be used to train LLMs.[51],[52]

- Computing power advantage: The importance of materials such as chips and the location of data centres in developing and running LLMs means economies of scale apply. Only a few companies have the cloud and computing resources necessary to develop AI system as sophisticated and competitive as the leading LLMs. This means AI start-ups and other new entrants are likely to need to license infrastructure from large providers such as Microsoft, Google or Amazon. These providers may be their competitors in providing generative AI and LLM services.[53] There is also a relatively small pool of highly-skilled tech workers from which firms seeking to develop these models can recruit.

- Financial resources: For example, Microsoft recently announced it will pay to defend any customers of its Copilot AI software against copyright lawsuits, as well as the amount of any adverse judgments.[54] This assumption of legal liability could potentially become a barrier to entry for new market participants with limited financial resources.

- Other relevant characteristics may include economies of scale and ‘positive feedback loops’. In these loops, a service’s performance improves as more people use it. This leads to increased popularity and further performance improvements.

4.3.1 Competition among search services

People are speculating that new services based on LLMs may disrupt Google’s enduring dominance[55] in the search engine market by providing more relevant, direct and comprehensive responses to user queries. The launch of the LLM-powered ‘new Bing’ has been described as a fight for search engine supremacy between Google and Microsoft.[56] After Microsoft announced ‘new Bing’, the Bing app’s downloads increased ten-fold.[57] In April 2023, Samsung considered replacing Google with Bing as the default search engine on its mobile devices,[58] and in May 2023, Microsoft made Bing the default search engine for ChatGPT Plus users.[59]

Google’s Bard LLM chatbot is separate from its search engine services, but Google is trialling its new ‘Search Generative Experience’. This feature provides AI-assisted answers to a user query before showing standard search results.[60]

However, the potential for LLM technology to disrupt the search engine market may have been overstated.

- Firstly, existing search services, such as Google Search, already have similar features, such as snippet summaries of website content and responses to questions from users or predicted by the search service. Secondly, the limitations of LLM-based services in providing accurate responses may discourage people from using them.[61]

- Moreover, digital platforms such as Google and Microsoft, which are leading LLM developers, often acquire or copy new technologies quickly.[62]They then leverage these technologies to maintain and defend their market positions in various digital platform services. For example, Microsoft has reportedly threatened to restrict access to Bing’s search data for customers developing competitors to GPT-4.[63]

- The difficulties smaller firms face in overcoming these obstacles are highlighted by the example of Neeva. The subscription-based search engine announced in May 2023 that it would withdraw from the market on 2 June 2023, despite its investment in LLM technology to be ‘the first search engine to provide cited, real-time AI answers to a majority of queries’.[64]

4.3.2 Other digital platform services, and digital platform ecosystems

Outside of search, using LLMs can increase a user’s interaction with particular digital platforms. Over time, this may make it more difficult for users to leave these platforms. For example, to use the new Bing, users need to join a waitlist with a Microsoft account. This process encourages the user to stay logged in or download an app for password-free sign in. Likewise, using Google’s Bard requires a Google account sign-in.[65] In general, LLMs and other generative AI services are becoming part of already-dominant platforms’ services, partly through investment and acquisitions.[66] Such investments include Google’s interests in DeepMind[67] and Anthropic,[68] Microsoft’s significant investments in OpenAI[69] and Amazon’s investment in Anthropic.[70]

LLMs may also affect competition in other digital platform service markets, by giving competitive advantages to firms with the most effective LLMs. This could happen in markets for:

- Browser services: Their use is linked to search services. LLM-powered search functions can be incorporated directly into browsers, as Microsoft has done with the new Bing and its Edge browser,[71]and Google as announced with Search.[72]

- Services that incorporate search functions; This includes app stores and online retail marketplaces. LLMs can potentially reduce search costs for users and increase sales for sellers by more effectively matching shoppers with products they’re most likely to buy.[73]

- Social media services and advertising-funded services: LLMs could allow advertisers or platforms to better target their display ads or sponsored social media posts.

- Productivity suite services: Popular enterprise applications (such as email or word processing) may default to using a service provider’s own services when generating LLM-powered content.

4.3.3 Potential to increase anti-competitive conduct

LLMs could allow big digital platforms to strengthen and expand their market power by continuing to engage in difficult-to-detect anti-competitive practices the ACCC has previously observed. For example, large digital platforms that use LLMs could engage in:

- Self-preferencing: This could make it more difficult for users to tell when LLM-based chatbots are making sponsored recommendations or referring to products or services offered by the same company that operates the chatbot.

- Tying: This could involve linking the availability of ‘must-have’ LLM services to use of other services, such as browsers or search engines.

- Data access restriction: This could limit the training of rival LLMs, such as restricting their ability to respond to queries about recent events.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has also suggested LLMs could facilitate anti-competitive behaviour in broader markets, such as setting prices, determining bids, or sharing markets.[74] This includes:

- Generative collusion: This could involve accessing rival chatbots’ prices and other business contract terms and suggesting changes to their own terms accordingly.

- Platform collusion: This could involve competitors in a different market providing an LLM with commercially sensitive pricing data and obtaining similar data about others by putting relevant questions to the chatbot.[75]

4.4 Media and the information environment

4.4.1 Risks for the information environment

LLMs can make it easier and cheaper to produce news and other information sources, but they also pose several risks.

- LLMs can reinforce and reproduce biases present in their training data, which can distort the quality of the information they provide.[76]

- LLMs can ‘generate outputs that sound authoritative but are factually incorrect.[77] Called ‘hallucinations’, these outputs can be difficult for both experts and non-experts to detect.[78]

- This can lead to the spread of misinformation, potentially causing harm. For example, in June 2023, a US man initiated defamation proceedings against OpenAI, claiming ChatGPT had falsely told a journalist he had been sued for embezzlement.[79]

- While some LLMs may eventually access and interpret real-time data, they are generally trained with data that is current to a certain point in time. This means they might struggle to provide accurate information about current events or real-time data. As a result, using LLMs for news may lead to the spread of outdated and unreliable information.[80]

- Given the ease with which LLMs can generate information, bad actors could use them to disseminate misinformation on a large scale in several ways:

- LLMs can generate misinformation that mimics the styles of authoritative sources such as news outlets or government organisations.[81]

- LLMs could impact democratic and political processes by generating significant amounts of text that spread false information or propaganda at low cost. This content might appear more reliable than content generated by bots.[82]

- The widespread use of LLMs could further mislead people and disrupt the quality of public interest information.[83]

- In May 2023, NewsGuard identified 49 sites in 7 languages as ‘content farms’ that mostly or entirely used LLMs to generate articles. Some of these articles promoted false narratives such as vaccine conspiracy theories.[84] LLMs make it easier to generate these low-quality or deceptive websites.

LLMs can also impact news creators and other information sources by compiling their information (including content behind paywalls) into responses without compensation.[85] This effect now extends to search results, with AI presenting snapshots of information collected from sources across the internet without users needing to click website links. This has led to calls, such as by former ACCC Chair Rod Sims, for LLMs to be covered by Australia’s News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code.[86]

4.4.2 Benefits to the information environment

Conversely, LLMs can help improve trust and safety in the information environment, while also improving productivity and the viability of news production. LLMs can:

- serve as a learning tool to help a variety of learners, including primary school students, university students, group learners, remote learners, learners with disabilities, and those for whom English is a second language[87]

- create personalised news feeds or recommend content that is more relevant to users.[88]

- to help fact-checkers quickly synthesise and process large amounts of information.[89]

- support the creation and distribution of original journalism, including generating article ideas, interrogating large data sets, identifying errors or suggesting corrections, and reducing time spent on business processes and administration. The BBC and The Guardian have already used AI to generate hyper-local news stories.[90]

4.5 Privacy

4.5.1 Opacity in the handling of personal information

LLMs may collect, use, disclose and store personal information. This can happen during large-scale internet data scraping to prepare data for LLM pre-training or when a user submits personal information in their prompt to a chatbot.[91] If there are no clear details about how personal information is handled, people won’t understand the privacy risks when using the service.

4.5.2 Disclosure of inaccurate personal information

LLMs can sometimes produce incorrect or misleading outputs, including ‘hallucinations’.[92] This can lead to the creation of false information about individuals. For example, a mayor in regional Victoria is considering defamation action against OpenAI because ChatGPT falsely stated he was a guilty party in a foreign bribery scandal. In reality, he had been the whistleblower and he was never charged with a crime.[93]

4.5.3 Data scraping impacting control over personal information

LLMs are often trained on public data due to their large data needs. There are concerns about scraping information from public websites without the knowledge or consent of the content creators or subjects, which may include their personal information.[94]

Some commentators have also raised concerns about the limited ways for users to access or delete their personal information.[95] The industry has tried to address these issues by introducing certain features to their services. For example, some companies have introduced an ‘export’ function that allows users to request a copy of their stored information or a mechanism to request access to, correction of, deletion of or transfer of their personal information that may be included in the entity’s training data.[96]

4.5.4 Data breach risk

The vast amounts of data collected and stored by LLMs may increase the risks related to data breaches, especially when individuals disclose particularly sensitive data in their conversations with the LLM because they are not aware it is being retained.[97]

Using LLMs to generate malicious code noted above could also lead to an increased risk of data breaches.

4.5.5 Uses of personal information by LLMs

The use of personal information by LLMs can have particular impacts on individuals. For example, LLMs could be trained on large amounts of customer data to recognise consumer preferences, and then used to create personalised advertising content for individual users.[98] As noted above, LLMs may also produce discriminatory results.

4.6 Online safety

LLMs can impact online safety. They have the potential to create both risks and opportunities. These may be standalone or intersect with consumer protection, competition, the media and information environment, and privacy.

Some potential opportunities for LLMs and generative AI tools to enhance online safety include:

- detecting and moderating harmful online material more effectively and at scale

- enhancing learning opportunities and digital literacy skills

- establishing more effective and robust conversations about consent for data collection and use

- providing evidence-based scalable support that is easy to understand and age appropriate to meet the needs of young people, such as through helpline chatbots.

However, the possible threats from LLMs are not just theoretical. Real-world harms already exist. Some of these online safety risks and challenges are outlined below.

4.6.1 Abuse, bullying, harassment and hate at scale

LLMs can generate online abuse, hate and discriminatory content. This can harm society and harass individuals online. There’s a risk LLMs could automate these kinds of outputs at scale. Coupled with their ability to produce unique outputs, they could enable campaigns of hate speech or other harmful content that flood online platforms.[99]

4.6.2 Manipulation, impersonation, and exploitation

LLM-powered conversational agents can influence a person’s decisions because they can adapt and respond to data in real time.[100] This can manifest in a variety of harms. For example, a chatbot designed as an eating disorder hotline once encouraged a user to develop unhealthy eating habits.[101]

LLMs can also create fake personas or impersonations of people or organisations, making it easier to deceive and manipulate others online. They’ve been used to create convincing text for grooming,[102] catfishing[103]or sexual extortion[104]. The risk of impersonation increases when LLMs are combined with other forms of generative AI, such as image or voice generators.

They can also create terrorist and violent extremist content (TVEC) or terrorist propaganda.[105]

4.6.3 Age-inappropriate content

Some LLM chatbots, such as Snapchat’s My AI (which accumulated 150 million users out of 750 million Snapchat users from its release on 20 April 2023 to 11 June 2023)[106]may be providing users with age-inappropriate results. For example, they’ve told teenagers how to mask the smell of alcohol and marijuana or engage in sexual conduct.[107] There are also reports of the chatbot advising a user pretending to be 13-years-old on how to lie to her parents about meeting a 31-year-old man.[108]

To safeguard children and young people, it is essential to implement age-appropriate design, supported by robust age assurance measures. Services and features accessible to children should be designed with their rights, safety, and best interests in mind. Specific protections should be in place to reduce the chances of children encountering or being exploited to produce harmful content and activity.

4.6.4 Mitigations

Everyone involved – technology developers, downstream services that integrate or provide access to the technology (such as LLM-aided search engines and chatbots), regulators, researchers and the public – should be aware LLMs’ potential harms and play a role in addressing them.

Services can use various interventions and measures to minimise the risk of harm from deploying LLMs. A Safety by Design approach, based on core principles, is crucial for user safety and building trust with communities. Safety measures include well-resourced trust and safety teams, red-teaming and violet-teaming before deployment, routine stress tests with diverse teams to identify potential harms, digital watermarking of content, real-time support and reporting, regular evaluation, and third-party audits.[109]

Other ways to mitigate potential harms include developing models that draw on a wide range of perspectives and establishing evaluation metrics that actively address racial, gender, and other biases, while promoting value pluralism. It’s crucial to adopt holistic evaluation strategies to address various risks and biases.

For more detailed information on generative AI’s opportunities and risks to online safety, as well as specific Safety by Design interventions, refer to eSafety’s position statement on generative AI.[110]

5. Recent Australian Government developments

There have been notable developments from the Australian Government in 2023 in response to the growing popularity of LLM applications.

5.1 DISR discussion paper and NSTC-commissioned report

On 1 June 2023, the Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR) published a rapid response report on generative AI, commissioned by the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) as well as a discussion paper titled ‘Safe and responsible AI in Australia’.[111]

The paper explores potential regulatory responses to mitigate AI risks and invites feedback on Australia’s potential actions. It also considers existing and proposed approaches in the European Union, United Kingdom and United States.

5.2 eSafety decision on the draft Search Engine Services Code

In September 2023, the eSafety Commissioner registered the Internet Search Engine Services Online Safety Code (Class 1A and Class 1B Material), also known as the SES Code.

This decision was made after industry associations submitted a revised SES code to address the Commissioner’s concerns that an earlier draft did not adequately include generative AI features in search engine services.

The SES Code sets out specific measures for generative AI to minimise and prevent the generation of synthetic class 1A material (such as child sexual exploitation material or pro-terror content) on internet search engine services. It requires providers to:

- improve systems, processes and/or technologies to reduce safety risks related to synthetic materials generated by AI that might be accessible via their search engine service

- ensure that any AI-enabled features integrated into a search engine service, such as longer-form answers, summaries or materials, do not return search results containing child sexual abuse material

- clearly indicate when a user is interacting with any AI-enabled features.

The SES Code will come into effect in March 2024. Further information on what the SES Code will cover, including how it considers generative AI functionality, is available on eSafety’s website.[112]

5.3 Senate Select Committee on Foreign Interference through Social Media recommendation

On 2 August 2023, the Senate Select Committee on Foreign Interference through Social Media recommended the Australian Government investigate options to identify, prevent and disrupt AI-generated disinformation and foreign interference campaigns. This is in addition to the DISR’s consultation process on the safe and responsible use of AI technology.[113]

5.4 ACMA’s second report on digital platforms’ efforts under the Australian Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation

Given the rapid growth and adoption of generative AI technologies across a range of digital platform services, an ACMA report recommended that the Digital Industry Group Inc (DIGI) and signatories consider whether the current code adequately addresses the scope and impacts of this technology.

5.5 eSafety Commissioner’s Tech Trends paper on generative AI

eSafety regularly scans the horizon and consults with subject matter experts to guide its work. This allows eSafety to identify the online safety risks and benefits of emerging technologies, as well as the regulatory opportunities and challenges they may present.

In August 2023, eSafety released its new position statement on generative AI, examining LLMs and multimodal models. This statement, part of the Tech Trends workstream, provides an overview of the generative AI lifecycle, examples of its use and misuse, consideration of online safety risks and opportunities, as well as regulatory challenges and approaches. It also suggests specific Safety by Design interventions industry can adopt immediately to improve user safety and empowerment.

5.6 Inquiry into the use of generative AI in the Australian education system

In May 2023, the House Standing Committee on Employment, Education and Training started an investigation into the use of generative AI in Australia’s education system, including early childhood education, schools, and higher education sectors.

The inquiry is looking at the strengths and benefits of generative AI tools and how they can improve education outcomes. It’s also examining their impact on teaching and assessment practices, safe and ethical uses, how disadvantaged students can benefit, local and international practices and policies, and recommendations to manage the risks and guide the potential development of generative AI tools, including standards.

5.7 Australian Framework for Generative Artificial Intelligence in Schools

Commonwealth, States, Territories and the non-government school sector are also currently working together to develop a framework to help schools and education systems use AI.

6. Regulatory challenges

The growing use of LLMs may pose regulatory challenges. Australian regulators face difficulties in balancing innovation and regulation, enforcement, and keeping pace with evolving technology and business models.

- Challenges in balancing the need to promote innovation while protecting Australians: Regulators need technical expertise to regulate AI effectively without stifling dynamism or hindering competition between LLM providers.[114] However, obtaining independent advice can be a challenge because technical expertise often lies within the entities being regulated.

- Cross-jurisdictional challenges: More widespread use of AI by regulated entities can exacerbate cross-jurisdictional enforcement issues. Australian regulators need to collaborate with international counterparts while protecting Australians. They also face challenges in using their investigative powers to access algorithms, code and other technical materials stored overseas.

- Challenges in keeping pace with evolving technology and business models:

- Generative AI is rapidly evolving, and so efforts to regulate it (including through policy developments or enforcement actions) face the risk of becoming quickly outdated as the nature, capabilities and uses of these services evolve.

- The ecosystems around generative AI are also in flux, requiring careful consideration of how best to allocate responsibility across relevant actors.

- The sheer size of LLMs poses significant challenges, such as auditing.[115]The ‘black box’ nature of generative AI systems can obscure accountability. It’s difficult to explain how LLMs generate specific outputs due to the use of deep learning, a technique based on multi-layered neural networks (discussed at 3.2 above). A range of regulatory and auditing approaches are being considered to address these challenges. To be effective, these should seek to overcome challenges in establishing consensus in risk definitions and methodologies across wide-ranging platforms.[116]

- LLMs can impact regulated areas of the economy. Regulators should continue to assess how current regulations apply to LLMs and provide guidance where necessary to make sure existing regulatory and enforcement tools remain effective. As noted in section 5, the DISR consultation on ‘Safe and responsible AI in Australia’ has started a whole-of-government consideration of these issues. The responses received, including DP-REG’s own submission, will guide government decisions on any regulatory and policy responses. As noted above, DP-REG’s joint submission, included as attachment A, examines more closely how the respective regulatory frameworks of DP-REG members apply to LLMs (and generative AI more broadly).

- Generative AI’s ability to produce large amounts of unique text can be misused, potentially disrupting public submission processes run by regulators and other government agencies. This misuse could put a strain on staff time and resources and make it difficult to accept and consider public submissions made in good faith.[117]

7. Next steps/future work

DP-REG member regulators will continue to monitor and consider developments in this space, in light of their individual regulatory responsibilities. For example, eSafety will explore how AI-related harms can be addressed through the upcoming review of the Online Safety Act 2021. The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts (DITRDCA) is leading this review, which is set to happen in 2024.

DP-REG members will also take part in government-wide discussions to plan Australia’s response to these technological developments.

8. Acknowledgements

DP-REG members acknowledge the contribution made by experts in sharing their insights on generative AI with the DP-REG forum in the context of preparing this paper. In particular, we thank the following experts:

- Dr Ke Deng, RMIT

- Dr Joanne Gray, University of Sydney

- Professor Mark Sanderson, RMIT

- Bill Simpson-Young, Gradient Institute

- Dr Aaron Snoswell, Queensland University of Technology

- Professor Kimberlee Weatherall, University of Sydney

- Professor Jenny Zhang, RMIT

9. DP-REG relevant workstreams and publications

ACMA

- ACMA, Natural language processing technologies in government: occasional paper, June 2021.

- ACMA, Artificial intelligence in communications and media: occasional paper, July 2020.

ACCC

- ACCC, September 2022 interim report of the Digital Platform Services Inquiry.

- ACCC, March 2023 interim report of the Digital Platform Services Inquiry.

eSafety

- eSafety, Generative AI – position statement, August 2023.

- eSafety, Submission – inquiry into the use of generative artificial intelligence in the Australian education system, July 2023.

- eSafety, Submission – Inquiry into artificial intelligence in NSW, October 2023.

OAIC

- OAIC, Guide to undertaking privacy impact assessments, OAIC website, 2 September 2021.

- OAIC, Guide to securing personal information, OAIC website, 5 June 2018.

- OAIC, Privacy impact assessment tool, OAIC website.

- OAIC et al., . Joint statement on data scraping and the protection of privacy, OAIC website 24 August 2023.

- OAIC, Department of Industry, Science and Resources – Safe and Responsible AI in Australia Discussion Paper – Submission by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner, OAIC website, 18 August 2023.

10. Key sources

- eSafety Commissioner, .Position Statement – Generative AI, August 2023

- G Bell et al., Rapid Response Information Report: Generative AI - language models (LLMs) and multimodal foundation models (MFMs), Australian Council of Learned Academies, 24 March 2023.

- AI Now Institute, 2023 Landscape – Executive Summary, 11 April 2023.

- L Rosenberg, The Manipulation Problem: Conversational AI as a Threat to Epistemic Agency, Conference: Generative AI and HCI Workshop CHI, April 2023.

- Human Technology Institute, The State of AI Governance in Australia, University of Technology Sydney, May 2023.

Attachment A

Endnotes

[1] Formerly ‘Twitter’.

[2]A language model is a mathematical model of a language – an equation describing the statistical relationships between words or characters. Given some starting words (called the ‘context’ or ‘prompt’), a language model can be used to predict what characters or words will follow from these starting words (called the ‘completion’ for that prompt) – similar to the ‘auto complete’ functionality in many smart phone messaging apps.

[3] Generative AI is a type of AI that can create content such as text, images, audio, video or data, usually in response to plain language prompts entered by a user, using ‘natural language processing’. Generative AI adopts a machine learning approach for turning inputs and outputs into new outputs by analysing extremely large data sets to derive relationships between inputs and outputs.

[4] Artificial Intelligence is the ability of computer software to perform tasks that are complex enough to simulate a level of capability or understanding usually associated with human intelligence.

[5] For example, note that LLMs may also be categorised as a type of ’foundation model‘. Some LLMs, such as OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Baidu‘s Ernie, are also described as multi-modal foundation models because their inputs or outputs may include other types of information as well as text. Nonetheless, for the sake of convenience, these models will be referred to as LLMs in this paper. See e.g. G Bell et al., Rapid Response Information Report: Generative AI - language models (LLMs) and multimodal foundation models (MFMs), Australian Council of Learned Academies, 24 March 2023, pp 2-3.

[6] Microsoft Bing Blogs, Confirmed: the new Bing runs on OpenAI’s GPT-4, 14 March 2023.

[7]AWS, Amazon Bedrock, accessed 16 May 2023.

[8]Microsoft, Azure AI, accessed 16 May 2023.

[9] Semafor, The secret history of Elon Musk, Sam Altman, and OpenAI, 15 March 2023. (paywalled)

[10] OpenAI, GPT-4 System Card, 23 March 2023.

[11] ZDNet, With GPT-4, OpenAI opts for secrecy versus disclosure, 16 March 2023.

[12] E Bender, T Gebru et al., On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?, Conference paper, March 2021.

[13]Alemohammad et al., Self-Consuming Generative Models Go MAD, 4 July 2023.

[14] Digital Information World, Chat GPT Achieved One Million Users in Record Time - Revolutionizing Time-Saving in Various Fields, 27 January 2023.

[15] Reuters, ChatGPT sets record for fastest-growing user base - analyst note, 3 February 2023.

[16] Similarweb, ChatGPT Grew Another 55.8% in March, Overtaking Bing and DuckDuckGo, 3 April 2023.

[17] Reuters, OpenAI tech gives Microsoft's Bing a boost in search battle with Google, 23 March 2023.

[18] Grandview Research, Generative AI Market Size Worth $109.37 Billion By 2030, December 2022.

[19] GlobeNewswire, Rapid Growth of Large Language Models Drives Generative AI Market to Projected $51.8 Billion by 2028, 27 April 2023.

[20]Microsoft and Tech Council of Australia, Australia’s Generative AI opportunity, July 2023.

[21]G Bell et al., Rapid Response Information Report: Generative AI - language models (LLMs) and multimodal foundation models (MFMs), Australian Council of Learned Academies, 24 March 2023, p 9.

[22] The Telegraph, Advanced AI ‘could kill everyone’, warn Oxford researchers, 25 January 2023.

[23] Due.com, 5 Unexpected Ways AI Can Save the World, 17 January 2022.

[24] Centre for AI Safety, Statement on AI Risk: AI experts and public figures express their concern about AI risk, 2023.

[25] The Atlantic, AI doomerism is a decoy, 2 June 2023.

[26] Norton, Special Issue Norton Cyber Safety Pulse Report – The Cyber Risks of ChatGPT, 2 March 2023.

[27] The Guardian, AI chatbots making it harder to spot phishing emails, say experts, 30 March 2023.

[28]McAfee, ChatGPT: A scammer’s newest tool, 25 January 2023; Eydle, How Generative AI is Fueling Social Media Scams, 18 May 2023.

[29] New York Times, Lina Khan: We Must Regulate A.I. Here’s How, 3 May 2023. (paywalled)

[30] McAfee, ChatGPT: A scammer’s newest tool, 25 January 2023.

[31] Mashable, Scammers are spoofing ChatGPT to spread malware, 23 February 2023; The Verge, YouTuber trains AI bot on 4chan’s pile o’ bile with entirely predictable results, 9 June 2022.

[32] ABC News, Experts say AI scams are on the rise as criminals use voice cloning, phishing and technologies like ChatGPT to trick people, 12 April 2023.

[33] Norton, Special Issue Norton Cyber Safety Pulse Report – The Cyber Risks of ChatGPT2 March 2023.

[34] OpenAI, Snapshot of ChatGPT model behaviour guidelines, July 2022.

[35] Tech Policy Press, Ten Legal and Business Risks of Chatbots and Generative AI, 28 February 2023.

[36] Axios, AI’s scariest mystery, 30 July 2023.

[37] Sydney Morning Herald, Mum, help: Nina made three bank transfers before realising she had been scammed, 19 March 2023.

[38]Shaping Design, The fascinating origins of Lorem ipsum and how generative AI could kill it, 15 February 2023.

[39] The Guardian, Chatbot ‘journalists’ found running almost 50 AI-generated content farms, 3 May 2023.

[40]Harvard Business Review, How Will We Prevent AI-Based Forgery?, 1 March 2019.

[41] See, for example, ACCC, Digital platform services inquiry – September 2022 interim report – Regulatory reform, September 2022, p 8.

[42] Human Technology Institute, The State of AI Governance in Australia, University of Technology Sydney, May 2023, p 6.

[43] For example, Reuters, Alphabet shares dive after Google AI chatbot Bard flubs answer in ad, 6 February 2023. See also, as to the potentially US-centric nature of generative AI products, AFR, I tried Bing’s ChatGPT. Its Aussie results are a bin fire, 20 February 2023. (paywalled)

[44] FTC, Keep your AI claims in check, 27 February 2023.

[45] FTC, Keep your AI claims in check, 27 February 2023.

[46] IE University, ChatGPT and the Decline of Critical Thinking, 27 January 2023.

[47] See (n 2).

[48] Thibault Schrepel and Alex Pentland, Competition Between AI Foundation Models:

Dynamics and Policy Recommendations, 28 June 2023.

[49] AI Now Institute, 2023 Landscape – Executive Summary, 11 April 2023, p 6.

[50] In the context of Large Language Models, a 'hallucination' is a failed attempt to predict a suitable response to an input. See CSIRO, How AI hallucinates, 18 June 2023.

[51] Discussion at the ChatLLM23 conference in Sydney on 28 April 2023.

[52]Reddit recently announced new charges for Application Programming Interface (API) access to prevent firms training LLM models on its library of public posts (see Platformer, Reddit goes dark, 13 June 2023). X also recently removed public access to its content for internet users without an X account, and ended existing arrangements with Open AI to provide access to X data due to insufficient compensation (see Business Insider, Elon Musk cut off OpenAI’s access to Twitter data, 29 April 2023). Also see Guardian, New York Times, CNN and Australia’s ABC block OpenAI’s GPTBot web crawler from accessing content, 25 August 2023.

[53] AI Now Institute, 2023 Landscape – Executive Summary, 11 April 2023, p 6.

[54] Microsoft, Microsoft announces new Copilot Copyright Commitment for customers, 7 September 2023.

[55] The ACCC has previously concluded, as part of the Digital Platforms Inquiry 2017-2019, that Google has significant market power in search services. The ACCC estimated in 2021 that Google had a market share of 94% in search services in Australia, as part of the Third interim report of the DPSI of September 2021. Google is the pre-set default search engine on the overwhelming majority of browsers and other search access points (including search widgets, apps and voice assistants) on devices supplied in Australia. Google Search is the pre-set default search engine on both Google Chrome and Apple Safari, the leading suppliers of browsers in Australia.

[56] Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Google reveals AI search tech Bard, as Microsoft adds ChatGPT to Bing in the fight for search engine supremacy, 7 February 2023.

[57] TechCrunch, Bing’s app sees a 10x jump in downloads after Microsoft’s AI news, 9 February 2023.

[58]New York Times, Google Devising Radical Search Changes to Beat Back A.I. Rivals, 16 April 2023. (paywalled)

[59] Search Engine Land, Bing to be default search engine on Open AI’s ChatGPT, 23 May 2023.

[60] The Verge, The AI takeover of Google Search starts now, 11 May 2023.

[61] OpenAI, WebGPT: Improving the factual accuracy of language models through web browsing, 16 December 2021; Teche, Macquarie University, Why does ChatGPT generate fake references?, 20 February 2023.

[62] For example, Facebook’s introduction of reels and Instagram’s introduction of stories to compete with TikTok’s video style.

[63] Leah Nylen and Dina Bass, Microsoft Threatens to Restrict Data in Rival AI Search, 24 March 2023.

[64] sridhar, Post, 21 May 2023.

[65]Google Support, Use Bard, accessed 3 May 2023.

[66] Australian Financial Review, Generative AI magnifies urgency of regulating big tech platforms, 25 May 2023. (paywalled)

[67] TechCrunch, Google Acquires Artificial Intelligence Startup DeepMind For More Than $500 Million, 27 January 2014.

[68] Los Angeles Times, Google invests almost $400 million in ChatGPT rival Anthropic, 3 February 2023.

[69]CNBC, Microsoft announces new multibillion-dollar investment in ChatGPT-maker OpenAI, 23 January 2023.

[70] BBC News, Amazon takes on Microsoft as it invests billions in Anthropic, 25 September 2023.

[71]Microsoft, Reinventing search with a new AI-powered Microsoft Bing and Edge, your copilot for the web, 7 February 2023.

[72]Google, Supercharging Search with generative AI, May 10 2023.

[73] Microsoft, Azure OpenAI service, accessed 9 March 2023.

[74] OECD, Algorithmic Competition, 2023, chapter 3.

[75] DLA Piper, Chat GPT and competition law: Initial thoughts and questions, 24 March 2023.

[76]The Verge, As conservatives criticize ‘woke AI,’ here are ChatGPT’s rules for answering culture war queries, 17 February 2023; CBS News, ChatGPT and large language model bias, 5 March 2023; Wired, Review: We Put ChatGPT, Bing Chat, and Bard to the Test, 30 March 2023.

[77] E Bender, T Gebru et al., On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?, Conference paper, March 2021.

[78]The Galactica AI model was trained on scientific knowledge – but it spat out alarmingly plausible nonsense (theconversation.com).

[79] Bloomberg Law, OpenAI Hit With First Defamation Suit Over ChatGPT Hallucination, 8 June 2023. (paywalled)

[80] Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and University of Oxford, Is ChatGPT a threat or an opportunity for journalism? Five AI experts weigh in, 23 March 2023.

[81]NewsGuard, Despite OpenAI’s Promises, the Company’s New AI Tool Produces Misinformation More Frequently, and More Persuasively, than its Predecessor, March 2023; A Patel and J Sattler, Creatively malicious prompt engineering, WithSecure Intelligence, January 2023; The Guardian, ChatGPT is making up fake Guardian articles. Here’s how we’re responding, 6 April 2023; J Goldstein, G Sastry et al., Generative Language Models and Automated Influence Operations: Emerging Threats and Potential Mitigations, January 2023; The New York Times, Disinformation Researchers Raise Alarms About A.I. Chatbots, 8 February 2023 (last updated 13 February 2023). (paywalled)

[82] J Goldstein, G Sastry et al., Generative Language Models and Automated Influence Operations: Emerging Threats and Potential Mitigations, January 2023; BBC News, Could AI swamp social media with fake accounts?, 14 February 2023.

[83] IEEE Spectrum, Hallucinations Could Blunt ChatGPT’s Success, 13 March 2023; The Guardian, A fake news frenzy: why ChatGPT could be disastrous for truth in journalism, 3 March 2023.

[84]The Guardian, Chatbot ‘journalists’ found running almost 50 AI-generated content farms, 3 May 2023.

[85] Global Competition Review, Experts warn of antitrust risks from generative AI, 18 April 2023.

[86]Australian Financial Review, AI should pay for news content: Rod Sims, 23 April 2023.

[87] Science Direct, ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education, April 2023.

[88] Generative AI in the Newsroom, What Could ChatGPT Do for News Production?, 15 February 2023.

[89]Google Bard fails to deliver on its promise — even after latest updates | VentureBeat

[90]Financial Times, Daily Mirror publisher explores using ChatGPT to help write local news, 18 February 2023.

[91] Bell, G., Burgess, J., Thomas, J., and Sadiq, S, Rapid Response Information Report: Generative AI - language models (LLMs) and multimodal foundation models (MFMs), 24 March 2023. (paywalled)

[92] Bell, G., Burgess, J., Thomas, J., and Sadiq, S, Rapid Response Information Report: Generative AI - language models (LLMs) and multimodal foundation models (MFMs), 24 March 2023.

[93] ABC News, Hepburn mayor may sue OpenAI for defamation over false ChatGPT claims, 6 April 2023.

[94] InnovationAus, ChatGPT is a data privacy nightmare, 10 February 2023. Also see Bell, G., Burgess, J., Thomas, J., and Sadiq, S, Rapid Response Information Report: Generative AI - language models (LLMs) and multimodal foundation models (MFMs), 24 March 2023.

[95] InnovationAus, ChatGPT is a data privacy nightmare, 10 February 2023; Avast, Is ChatGPT’s use of people’s data even legal?, 1 February 2023.

[96]See for example OpenAI, New ways to manage your data in ChatGPT, 25 April 2023; OpenAI, Privacy Policy, 23 June 2023.

[97] Bell, G., Burgess, J., Thomas, J., and Sadiq, S, Rapid Response Information Report: Generative AI - language models (LLMs) and multimodal foundation models (MFMs), 24 March 2023; National Cyber Security Centre (UK), ChatGPT and large language models: what’s the risk?, 14 March 2023.

[98] L Aguilera, Generative AI and LLMs and Digital Marketing, LinkedIn, 23 February 2023.

[99]eSafety Commissioner, Generative AI – position statement, August 2023.

[100] L Rosenberg, The Manipulation Problem: Conversational AI as a Threat to Epistemic Agency, Conference paper, April 2023.

[101]Vice, ‘He Would Still Be Here’: Man Dies by Suicide After Talking with AI Chatbot, Widow Says, 31 March 2023.

[102]eSafety Commissioner, Child Grooming and Unwanted Contact fact sheet, September 2023

[103] eSafety Commissioner, Catfishing, September 2023

[104] eSafety Commissioner, Deal with Sextortion, September 2023

[105]Europol, ChatGPT: The impact of Large Language Models on Law Enforcement, 27 March 2023.

[106] Snap, Early Insights on My AI, 11 June 2023.

[107]The Washington Post, Snapchat tried to make a safe AI. It chats with me about booze and sex, 14 March 2023.

[108] The Washington Post, Snapchat tried to make a safe AI. It chats with me about booze and sex, 14 March 2023.

[109] eSafety Commissioner, Generative AI – position statement, August 2023.

[110] eSafety Commissioner, Generative AI – position statement, August 2023.

[111] Department of Industry, Science and Resources, Safe and responsible AI in Australia – Discussion paper, June 2023.

[112] eSafety Commissioner, Fact sheet: Registration of the Internet Search Engine Code, 8 September 2023.

[113] Parliament of Australia, List of Recommendations, 2 August 2023.

[114] Thibault Schrepel and Alex Pentland, Competition Between AI Foundation Models: Dynamics and Policy Recommendations, 28 June 2023.

[115] I Solaiman, The Gradient of Generative AI Release: Methods and Considerations, Hugging Face, 5 February 2023.

[116] AI Now Institute, Algorithmic Accountability: Moving Beyond Audits, 11 April 2023.

[117]GW Regulatory Studies Center, Will ChatGPT Break Notice and Comment for Regulations?, 13 January 2023.